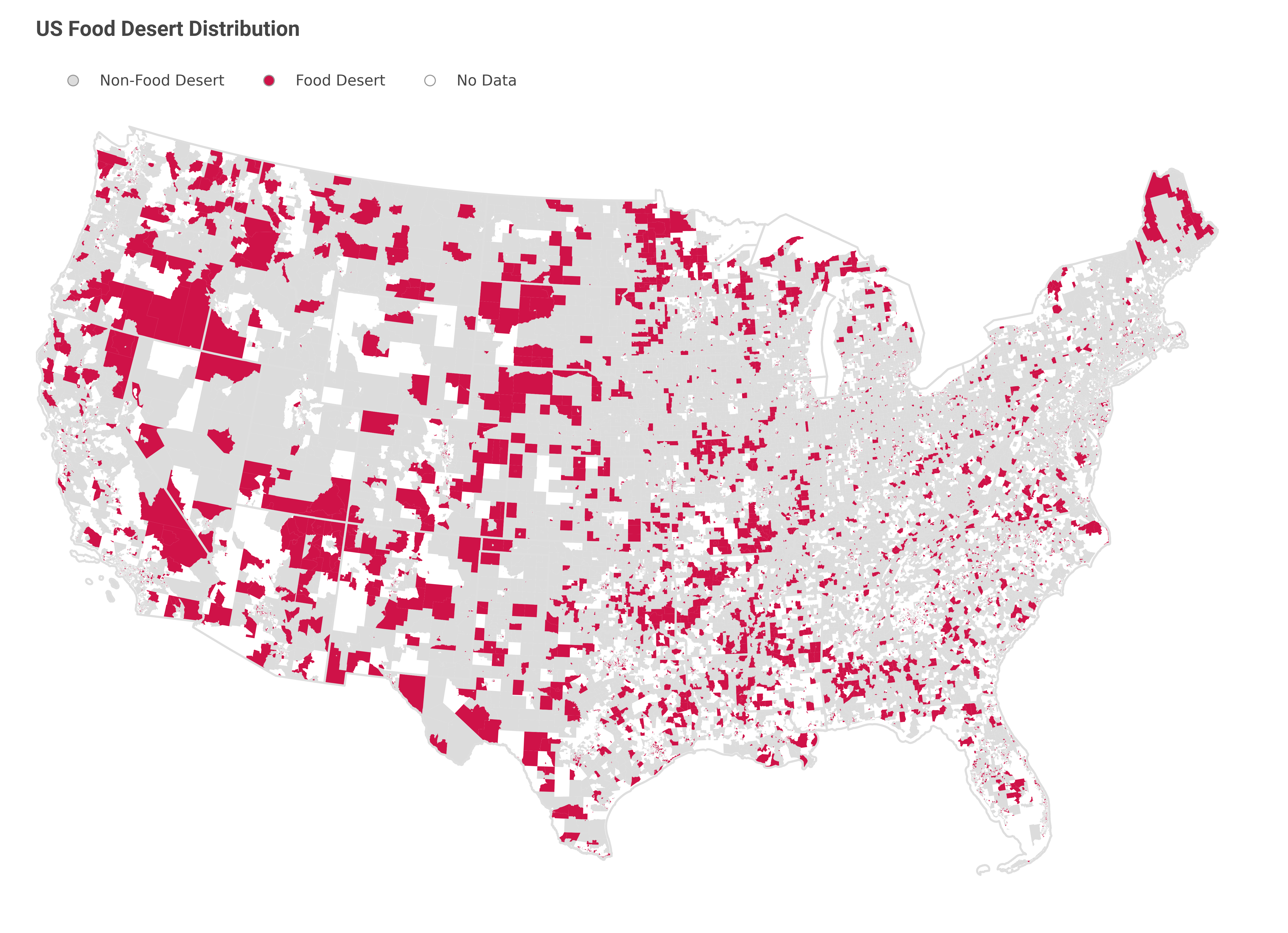

Commonly known as food deserts, Low-Income and Low-Access Tracts are defined by the US Department of Agriculture as census tracts “characterised by at least 500 people and/or 33% of the tract population residing more than 1 mile from a supermarket or large grocery in urban areas, and more than 10 miles in rural area”. Due to the lack of access to healthy foods, food desert residents are exposed to a higher risk of chronic diseases. Coupled with the income status residents often find themselves in, it creates a vicious cycle that traps residents in a poverty cycle.

The USDA has conducted three series of Food Access Research Atlas since 2006. As detailed in the documentation, the classification of census tracts into food deserts or not requires a series of census data and a complete list of fully operational food outlets that represent sources of affordable and nutritious food. However, the exact methodology has not been published. Given the data source employed, however, one could reasonably guess that sptial analysis was employed where each household is mapped to its closest food outlet and the distance is computed using conventional GIS programmes. This is of course a lengthy process and the reliability of the food outlet data could be questioned, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic.

This is where the machine learning methods may come into play. The American Community Survey provides an ongoing data source that enables more time-sensitive estimation of the location of food deserts. Using a myriad of social-demographic data and geospatial data, there is a potential to derive patterns for identifying food deserts. Naturally, these machine learning models should take into account income level and spatial data of some sort. One natural contender would be the area of the census tract.

Using a simple decision tree algorithm where the census tract is segmented into two groups by iteratively evaluating them using a set of true or false questions, we yielded a model that can correctly classify 33% of previously unseen food deserts. No doubt, this result shows that the machine learning methods are not up for the task. Using a more complex model, such as a random forest does not improve the performance either.

Nonetheless, the result from the decision tree shows that income and census tract size are the two most important features to consider when predicting the prevalence of food deserts. Moving forward, we may consider including other social-demographic variables and consider different ways to engineer features that provide better input and proxies that help segregate food deserts from non-food deserts.

Author’s Note:

For detailed methodologies for data acquisition, manipulation and the training of machine learning models, you can visit the respective GitHub Repository.